Filters Off: Writing in Deep Point of View

How to Close the Distance Between Reader and Character

Why are found footage movies, first-person shooter games, and Choose Your Own Adventure stories so popular?

Because people don’t just want to watch a story. They want to smell the food, sweat in the heat, and shiver with fear. They don’t want a front-row seat—they want to be the actor onstage, sweating under the lights.

For fiction writers, the best way to deliver that experience is to write in Deep Point of View (DPOV).

What is Deep POV?

DPOV is a writing technique that puts the reader directly behind the character’s eyes, hands on the wheel, foot on the gas. It relies on "show, don’t tell," sensory immersion, active emotion—and most importantly, the removal of filters that create distance between the reader and the character’s inner world.

Let’s look at a few examples to see the difference DPOV makes.

First Person Example

Standard First Person POV:

I watched as Kelsey went over to talk to Greg, knowing her plans to steal his affection. I always feared she would betray me.

First Person DPOV:

Kelsey walks straight to Greg. My stomach drops. One hand steals him. The other stabs me in the back.

Third Person Example

Standard Third Person POV:

Greg sprinted to the gym’s side door, desperate to escape this awful dance before Susan could kick his ass for dancing with Kelsey. He pushed the metal latch, but it was locked. His only chance was to get to the front door before she caught him.

Third Person DPOV:

Greg sprints to the gym’s side door. Susan’s gonna kill him. Why wouldn’t she? He danced with Kelsey right in front of her. Idiot. His hand hits the cold latch—nothing. Locked. The front door looks like a mile away. Move!

DPOV makes the writing more immediate, visceral, and emotionally engaging. It takes a bit of practice—especially if you’ve been writing in passive voice—but once you find your groove, it brings your fiction to life like few other techniques.

Three Techniques to Write in DPOV

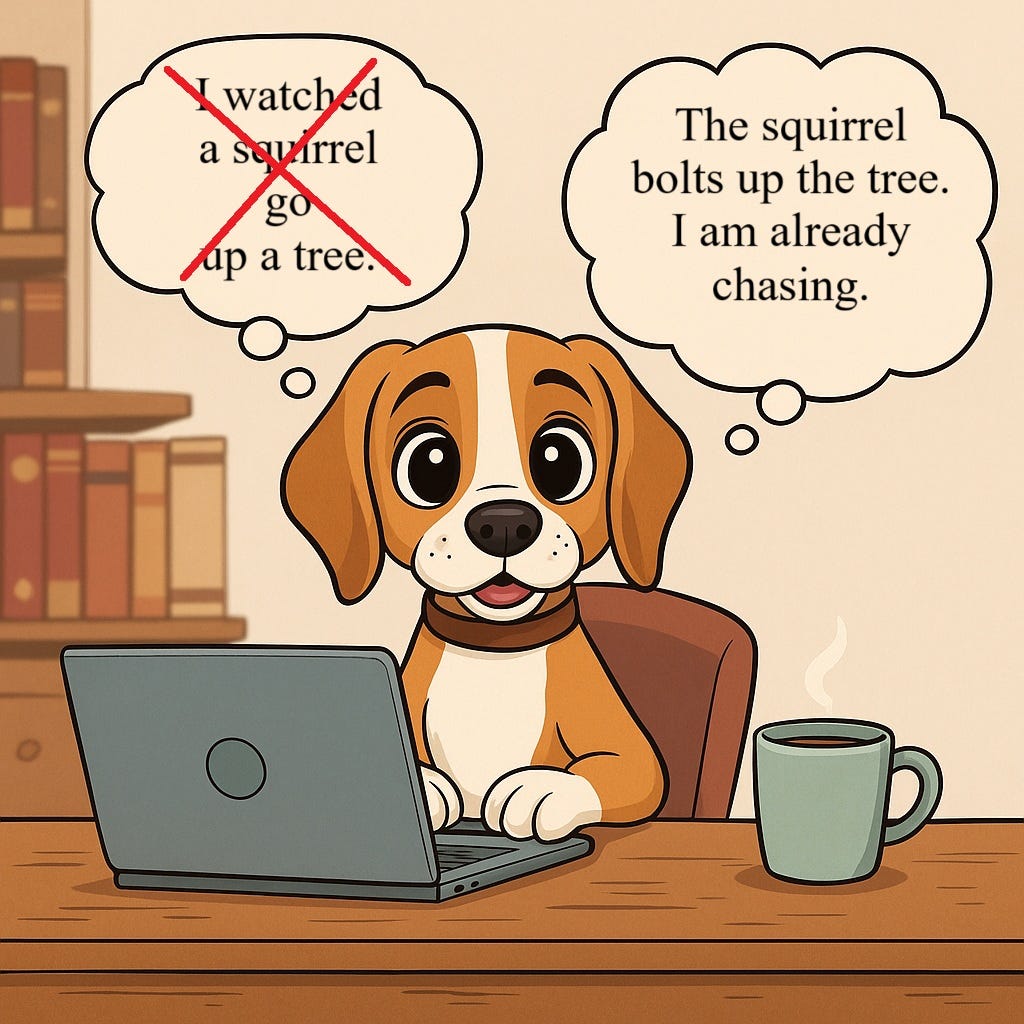

1. Lose the Filter Words

Filter words describe a character experiencing something, rather than letting the reader experience it with them. These include:

watched, heard, felt, saw, knew, thought, realized, remembered, noticed, hoped.

These words are like windows with smudged glass—they blur the scene.

With filter:

Seeing him by the door, Abbie remembered Greg said she wasn’t pretty enough.

Without filter (DPOV):

Greg stood by the door. He once said Abbie wasn’t pretty enough for him.

2. Watch Out for Adverbs

Adverbs are the seasoning of storytelling—used sparingly, they can sharpen a sentence. But overused, they drown your prose in soggy description. In DPOV, adverbs often signal a missed opportunity to show instead of tell.

Let’s take a look:

With adverb and filter:

Seeing him by the door, Abbie remembered sadly that Greg said she wasn’t pretty enough.

DPOV version:

Greg stood by the door. He once said Abbie wasn’t pretty enough for him.

The adverb “sadly” tells the reader how to feel instead of letting them feel it. Trust your reader to pick up the emotion through context, image, and tone—not stage directions.

3. Ditch Emotion Labels

Telling a reader a character is angry, sad, or scared is just that—telling. But describe the sensations of those emotions? Now we’re in the bloodstream.

With label:

Seeing him treat Susan that way made Abbie so angry.

DPOV:

The way Greg treated Susan turned Abbie into a boiling cauldron.

Labeled emotion:

Kelsey was stunning and so perfect. Beside her, I felt inferior and sad.

DPOV:

Kelsey stood radiant, flawless. Next to her, I was a sagging paper bag—empty, crumpled, nothing.

4. Use Dialogue Tags with Care (and Don’t Fear “Said”)

Dialogue tags like he shouted, she whispered, they cooed, can feel like neon signs blinking “YOU ARE READING.” They tug the reader out of the story and slow the pace.

With unnecessary tag:

“I hate you all,” Greg shouted.

DPOV:

“I hate you all!” Greg’s voice bounced off windows in a classroom two halls away.

With fancy tag:

“We should go somewhere more private,” Kelsey whispered seductively.

DPOV:

Kelsey leaned into Greg’s ear, her breath warm. “Why don’t we go somewhere more private?”

But don’t abandon “said.” Despite rumors that “said is dead”, it’s actually one of the most invisible, effective tools in a writer’s kit. Readers skip right over it, keeping their eyes on the scene. Use it when it helps clarity. Lose it when the flow is obvious.

If you haven’t written in DPOV before, start small. Take a few paragraphs from an old draft and rewrite them using these techniques. You’ll be surprised how quickly the rhythm becomes second nature—and how your characters start to live and breathe on the page.

Because you’re not just telling a story. You’re handing the reader the keys, opening the car door, and saying—drive.